From slang to algospeak: How TikTok is reshaping language

With over 1.8 billion monthly users, TikTok has significantly impacted various aspects of culture. In publishing, for example, book sales surge based on what trends on #BookTok. Even musicians adapt the structure of their tracks to suit the ever-so-powerful algorithm.

But we’d be ‘delulu’ to think it stops there. TikTok is accelerating the evolution of language in real time too by creating new vocabulary and encouraging self-censorship through coded language (‘algospeak’). So, the question is: how are these shifts happening, and are they bringing us together or just dividing us?

- TikTok, the slang engine of Gen Z

- The multilingual meme boom and cross-cultural expression

- When language becomes a barrier: The digital divide

TikTok, the slang engine of Gen Z

“TikTok isn’t just where slang lives—it’s where it’s born and distributed globally overnight.”

— Dr. Gretchen McCulloch, Internet Linguist and author of Because Internet

One of the most significant ways TikTok has impacted language is by introducing new vocabulary, particularly Gen Z slang. These terms often emerge from creators who strategically shape their speech to bypass content moderation, stimulate a sense of community or simply fish for a viral moment. This trend is further accelerated by constant exposure to memes and powerhouse influencers like MrBeast and Kimberly Loaiza.

Some popular TikTok-driven English slang words include:

- rizz: charisma (popularized by YouTuber Kai Cenat)

- delulu: delusional

- POV (Point of View): from the creator’s perspective

- face card: someone who gets what they want because of their looks

- mid: mediocre

- NPC (Non-Player Character): someone who lacks authenticity

- dupe: a cheaper imitation of a high-end product

- tea: gossip

- it’s giving…: something that evokes a particular ‘vibe’ (‘It’s giving Madonna’)

The multilingual meme boom and cross-cultural expression

Thanks to its technology and diverse creator pool, TikTok has become a space where users build cross-cultural bridges through language. Some of the avenues that have led to this are:

Blending languages for humor and connection

TikTok is, of course, a major global stage for shared humor, such as memes and viral trends. With a staggering reach across more than 150 countries. and an auto-translation tool that supports more than 15 languages, it’s a prime channel for comedic content that crosses language barriers.

Many creators actively embrace this multilingual potential, switching between languages like English-French or using hybrids like Singlish. They might employ these mixes to highlight cultural differences or drive a joke home, as seen in memes like US mom vs. Mexican mom. Auto-generated subtitles often support this kind of content, making it more accessible to wider audiences and bringing cultures together.

Yet despite this linguistic diversity,, unsurprisingly, English continues to dominate the platform. While it’s difficult to assess the exact amount of English content on the platform, it was the top moderated language in 2024. This dominance can contribute to cultural homogenization by overshadowing local cultures and overexposing the English language, especially among TikTok’s core communities (Gen Z and Millenials). In Spanish-speaking countries like Mexico, for example, younger generations blend languages and adopt internet-specific anglicisms like postear (to post) or taggear (to tag).

Language as identity performance

Language also plays an essential role in identity performance, shaping how we present ourselves to others. It allows us to express our social or cultural backgrounds, aligning with or distancing ourselves from certain groups.

On TikTok, creators use language not only to communicate, but also to enhance a sense of belonging and cultural identity. For instance, we can find content exploring Mexico City’s queer slang, guides on K-pop fandom terminology and hundreds of memes highlighting cultural differences. In this way, users contribute to their community’s identity formation, reinforce cultural signifiers and connect with each other regardless of location.

When language becomes a barrier: The digital divide

While TikTok can be a space for community building, it can unintentionally alienate audiences in several key ways:

Slang as gatekeeping

Communities on TikTok and other platforms are developing distinct language norms, often separate from other societal groups. Acronyms like FYP (For you Page), OOMF (One of my Followers/Friends) and IYKYK (If you Know you Know) are widely used, and terms like ‘delulu’ and ‘tea’ have even made their way into IRL (In Real Life) conversations. This hyper-specialized slang can be hard for non-users or older generations to understand. The result? Difficulty engaging with content and a sense of exclusion from cultural conversations happening on and off the platform.

The rise of algospeak and hidden language

“The more TikTok slang evolves, the more it starts to resemble a subcultural dialect—intelligible to insiders, mystifying to others.”

— Prof. Ilana Gershon, Media Anthropologist, Indiana University

Another layer of linguistic complexity arises from content moderation. To adhere to community guidelines and avoid content removal or shadowbanning, creators practice self-censorship by employing coded language that dodges moderation. They use symbols, numbers or euphemisms to mask their messaging in what is called ‘algospeak’ (algorithm speak). This way, creators can discuss sensitive topics such as politics, mental health and crime while going undetected.

Nevertheless, this form of language might not be intelligible to casual social media users or outsiders, which can create communication obstacles.

Let’s look at some examples of algospeak:

- Dior bags: drones

- unalive: death

- seggs: sex

- depressi0n: depression

Echo chambers

While the in-group communication can have a positive impact on community bonds, it can also deepen divisions and create linguistic echo chambers. As users engage with specific kinds of slang or dialect, they may become siloed into particular content bubbles. This limits exposure to alternative perspectives and can create mutual incomprehension between online subcultures.

A new language era—or a cultural divide?

The reach and speed of platforms like TikTok have a significant impact on how younger generations communicate. Social media slang and algospeak are influencing language, with positive and negative consequences. While on one hand they can foster a sense of belonging, on the other they risk widening generational or cultural gaps or contribute to cultural homogenization. This phenomenon also means that cultural fluency now demands not just linguistic ability, but also social media literacy, which makes it harder for certain groups to access particular discussions.

As we look ahead, only time will tell if these shifts will permanently reshape language, and who they’ll bring on board.

Begin your personal language journey

- Courses tailored to your learning needs

- Qualified native-level teachers

- Expert-designed curriculum

- Live classes with small group sizes

German modal particles: The secret sauce to native-level fluency

If you’ve ever listened to a native German speaker and wondered, “What does ‘doch’ even mean here?”, welcome to the world of German modal particles. These little words — doch, mal, ja, halt — don’t translate easily, because they don’t carry meaning the way most words do. Instead, they add tone, emotion and nuance. Think of them as the seasoning in a German conversation; they’re not vital for structure, but they do add some necessary flavor.

- Why German modal particles matter for fluency

- Common German modal particles and their meanings

- How to use modal particles in a sentence

- FAQs

Why German modal particles matter for fluency

German modal particles (Modalpartikeln) make speech feel more relaxed, more emotional, more human. Natives sprinkle them in without thinking. Learners, meanwhile, are often left wondering why their technically correct German still sounds a bit robotic.

Fluency isn’t just about knowing words, but about learning and internalizing how people actually speak. And modal particles are everywhere in colloquial German. They can make a sentence sound softer (mal), more persuasive (doch), more obvious (ja) or more resigned (halt). You won’t see them in many textbooks, because they’re notoriously hard to explain. But in real life, they’re part of the fabric of the language.

Common German modal particles and their meanings

Let’s get to know the usual suspects. These are the most common German modal particles, and while their meanings shift slightly depending on context, here’s what they usually do:

‘Aber’ — Emphasis or contradiction

Aber does more work than its literal translation (“but”) might suggest. As a modal particle, aber adds emphasis or contradiction.

- Das ist aber schön! (That really is nice!)

‘Ja’ — Obviousness or shared knowledge

Ja is used to signal something that’s unarguably true.

- Du bist ja verrückt! (You’re obviously crazy!)

‘Wohl’ — Assumed truth or probability

Wohl adds a sense of assumption to a statement.

- Er wird wohl noch im Büro sein. (He’s probably still at the office.)

‘Doch’ — Contradiction or emphasis

Doch is the Swiss Army knife of modal particles, and can be used either for emphasis or to contradict a statement.

- Komm doch mit! (Come along, will you?)

- Das hast du doch schon gesehen (You’ve indeed seen that already.)

You can also use it by itself to reply to something, both contradicting and with emphasis.

- Du hast ja die Wohnung nicht geputzt! (You have obviously not cleaned the apartment!)

Doch! (I have!)

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

‘Halt’ and ‘eben’ — Resignation, acceptance

These two often get lumped together, as they can be used in somewhat interchangeable ways.

- Das ist halt so. (That’s just how it is.)

- Dann ist das eben so. (Well, so be it.)

‘Schon’ — Softeners, reassurance

Schon helps to soften what might otherwise sound blunt.

- Das wird schon klappen. (It’ll work out, don’t worry.)

‘Mal’ — Informality, casualness

Mal can make commands or requests sound more friendly.

- Guck mal! (Take a look!)

‘Denn’ — Used in questions for curiosity or surprise

Denn does not translate to “because” in this particular instance. In questions, it adds a sense of curiosity or surprise.

- Was machst du denn da? (What are you doing there?)

‘Nun’ — Structuring speech, soft transition

Nun helps transition gently into something.

- Nun, das ist eine gute Frage. (Well, that’s a good question.)

‘Schließlich’ — Logical reasoning (i.e., ‘after all’)

Schließlich adds a “we already know this” tone.

- Sie hat schließlich viel Erfahrung in diesem Bereich. (She does have a lot of experience in this area, after all.)

You don’t need to memorize all of these modal particles at once. But knowing what they mean and how they function in a typical sentence can help you hear them with new ears.

What our students of German say

How to use modal particles in a sentence

German modal particles may seem random, but there’s a rhythm to how they’re used. While they don’t follow strict grammar rules like verbs or cases, they do have patterns. You can’t just drop them anywhere and hope for the best.

Position

Modal particles usually appear after the verb, often in the second or third position in the sentence. They rarely sound natural at the very start or end of a sentence.

- Du bist ja müde. (You’re obviously tired.)

One particle is good. Two? Still good

Germans often stack modal particles, especially ones that naturally pair — like doch mal or ja wohl. The order tends to follow what sounds “right” to native ears.

- Geh doch mal schlafen! (Just go to sleep already!)

While modal particles make speech sound casual and natural, throwing five into a single sentence is indeed trying too hard. It’s better to pick one or two instead, and let them do the work.

Try listening to native speakers and reading dialogue-heavy texts. Eventually, you’ll start to feel where these words go, even if you can’t explain why.

What are modal particles in German?

They’re small words that add tone or attitude — like emphasis, surprise or softness — to a sentence without changing its basic meaning.

What is the difference between ‘doch’ and ‘ja’?

Doch often contradicts something or adds encouragement (e.g., “Come on, do it!”). Ja points out something obvious or shared (e.g., “You know it’s true.”).

Tiny words, big impact: Master German modal particles

Modal particles may be tiny, but they punch way above their weight when it comes to making your German sound fluent and natural. We’ve covered what they are and why they matter. You now know where they fit in a sentence, how they shape tone and even how they team up.

Modal particles don’t come easy at first, but the more you hear and use them, the more instinctive they become. And that’s exactly the kind of practice you can expect with Lingoda, where you can learn German from native-level teachers in real conversations.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

How to form indirect questions in German

Indirect questions are often delicately couched inside statements or paired with other questions. So, instead of asking, “Wo ist der Bahnhof?” (Where is the train station?), you might ask, “Können Sie mir sagen, wo der Bahnhof ist?”. It’s more or less the same question, but the indirect version is dressed up in an extra layer of nicety.

Because indirect questions are essential in formal and professional situations, understanding how to form them will seriously level up your spoken and written German. So, how do these elegant guys work? Let’s break it down.

- Direct vs. indirect questions

- Forming indirect questions in German

- Punctuation and syntax nuances

- Practical applications

- FAQs

Direct vs. indirect questions

Direct questions shoot straight from the hip. They typically take the form of a simple, plain statement followed by a question mark. To form a direct question in German, flip the word order so that the verb precedes the subject, like so:

- Wo wohnt sie? (Where does she live?)

Indirect questions, on the other hand, are more diplomatic. This requires some additional grammatical work, as indirect questions are generally tucked inside or paired with another clause — a polite request, statement or question about a question, for example:

- Kannst du mir sagen, wo sie wohnt? (Can you tell me where she lives?)

Here’s the main structural difference:

- In direct questions, the verb usually comes before the subject.

- In indirect questions, the verb goes to the end, like in a subordinate clause.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

Forming indirect questions in German

Indirect questions follow a clear logic — but when we’re dealing with German word order, even clear logic can seem puzzling at first! So, for the sake of clarity, we’ll break this down into manageable parts:

Structure and word order

In an indirect question, the question becomes part of a larger sentence. That means it behaves like a subordinate clause, and in German, that means the verb goes to the end. Compare the following two sentences, the first of which is a direct question and the second of which is an indirect version of that same question (albeit, one that’s disguised as a statement):

- Was machst du? (What are you doing?)

- Ich weiß nicht, was du machst. (I don’t know what you’re doing.)

The word order in the indirect question flips, because we’re embedding the question inside a statement.

Using ‘ob’ for yes/no questions

When an indirect question doesn’t start with a question word but nonetheless demands a “yes” or “no” answer, German uses the word “ob” (whether/if), like so:

- Kommst du morgen? (Are you coming tomorrow?)

- Ich weiß nicht, ob du morgen kommst. (I don’t know if you’re coming tomorrow.)

Here, “ob” sets up the subordinate clause containing the indirect question. The verb (kommst) goes to the end, as it always does in subordinate clauses.

Using ‘W’ questions

For questions that start with words like wann (when), wo (where), wie (how) and warum (why), just plug the question word into the indirect sentence — and, again, move that verb to the end:

- Warum lernst du Deutsch? (Why are you learning German?)

- Er fragt, warum du Deutsch lernst. (He asks why you’re learning German.)

The recipe is straightforward:

“W” question word + subject + end verb = indirect question

Once you learn the pattern, you’ll start spotting indirect questions everywhere.

What our students of German say

Punctuation and syntax nuances

As we’ve seen, indirect questions don’t always use question marks in German — though they’re still technically questions. The rule is simple:

- If the sentence is a statement that contains a question, use a period:

Ich weiß nicht, wann er kommt. (I don’t know when he’s coming.) - If the sentence is a question about a question, use a question mark:

Kannst du mir sagen, wann er kommt? (Can you tell me when he’s coming?)

It’s not about whether there’s a question word in the sentence, but whether the whole sentence is functioning as a question or not.

Practical applications

Everyday conversations

Indirect questions help keep things friendly, polite or just a bit less in-your-face. You’ll hear them all the time in casual chats:

- Weißt du, wo mein Handy ist? (Do you know where my phone is?)

- Kannst du mir sagen, wie spät es ist? (Can you tell me what time it is?)

The indirect formulation is especially useful when you need to ask for help or information without sounding too direct.

Formal and written communication

In emails, job interviews or academic contexts, indirect questions are the standard for sounding respectful and professional:

- Ich würde gerne wissen, ob die Unterlagen vollständig sind. (I’d like to know if the documents are complete.)

- Könnten Sie mir mitteilen, wann das Besprechung stattfindet? (Could you let me know when the meeting is taking place?)

Using indirect questions in writing shows a solid grasp of tone — and makes you sound like a grown-up in the best way.

What is an indirect question in German?

An indirect question is a question embedded in a statement or another question, with the verb moved to the end of the subordinate clause.

How do you use ‘ob’ in German?

Use ob to introduce yes-or-no indirect questions, like: Ich weiß nicht, ob er kommt. (I don’t know if he is coming.)

Start using indirect questions with confidence

Indirect questions in German may look like a grammatical detour, but they’re actually a shortcut to sounding more natural, polite and fluent. We’ve looked at how they differ from direct questions, how to form them using ob and “W” question words, and where to place that ever-important verb. We’ve also seen how useful they are — whether you’re casually asking a friend to pass the salt or writing a professional email.

Mastering indirect questions isn’t about memorizing rules — it’s about practicing them in real conversations. That’s where learning German with Lingoda’s small group classes pays off. You’ll get live feedback, flexible scheduling and plenty of chances to ask how and why (indirectly or otherwise).

Ready to put your polite German into action? Go ask someone where the train station is — but do it like a pro.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

High German vs. Low German: Key differences explained

Aside from their regional designations, German dialects are generally grouped into two categories: High German and Low German. These terms have nothing to do with how “correct” or “proper” the language is; rather, they reflect how German has developed and diverged across vast swaths of land and time.

In this article, you’ll learn the key differences between High German vs. Low German. We’ll clarify what these terms actually mean and discuss how they’ve shaped the German you hear today.

- What “High” and “Low” really mean

- A sound divide: The High German consonant shift

- A short timeline of German dialect evolution

- Key differences between High and Low German

- Cultural and linguistic importance today

- FAQ

What ‘High’ and ‘Low’ really mean

Germany, Switzerland, and Austria are home to a broad variety of German dialects. While most of these dialects get their name from the region they’re spoken in — Bavarian, for instance — German dialects are also classified into two different categories: High German and Low German.

When we talk about “High” versus “Low,” we’re not talking about a measure of quality or even correctness. Instead, these terms literally refer to height — as in, elevation.

High German dialects are spoken in the southern German uplands, a stretch of land that includes Bavaria, Austria, and Switzerland. Low German dialects are spoken in the northern German lowlands and can be heard across cities like Hamburg and Bremen and in northern states like Schleswig-Holstein.

Is High German the same as Standard German?

Here’s where it can get confusing. The term “High German” is also sometimes used to mean Standard German (Standarddeutsch or Hochdeutsch), the standard written and spoken language used in schools and media across Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. The reason for this is that Standard German is derived mainly from written dialects used in the High German dialect area, especially Saxony and Thuringia.

The geography of German dialects

Look at the North-South dialect map after 1945, and you’ll notice that the linguistic border between Low and High German runs from west (approximately at the latitude of Münster) to east.

In the north, across the German lowlands, people traditionally spoke various dialects of Low German (Plattdeutsch). These dialects developed separately from Standard German and share some linguistic features with Dutch and English.

In the central regions of the German-speaking world, you’ll hear High German varieties of places like Hesse, Thuringia and parts of the Rhineland. In the southern regions, especially in Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg, Austria and Switzerland, you’ll find Upper German dialects.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

A sound divide: The High German consonant shift

If High German and Low German dialects sound quite different, it largely owes to the High German consonant shift. This shift spread gradually from the southern uplands (i.e., the Alps and Central Germany) northward and is believed to have been mostly completed by around 800 CE.

As this shift took hold, words evolved. Appel (apple) became Apfel, while dat (that) evolved to das in High German. Some common German verbs, like machen (to do), retain their Low German flavor to this day (e.g. makken). As the shift didn’t happen in Low German regions, older forms of words with Saxon or Old High German roots were preserved and are still used in some northern regions of Germany.

Here’s how some consonants changed in High German after the consonant shift:

- p → pf or f

- t → ts or s

- k → ch

This is one of the defining features that separates High German variants (like Bavarian, Alemannic and Standard German) from Low German, which preserved the older sound system. To give you a better understanding of what these differences sound like, here’s a quick comparison between the dialects:

| Low German | High German | English |

| Wat maakt he dor? | Was macht er da? | What is he doing there? |

| Ik hebb dat nicht sehn. | Ich habe das nicht gesehen. | I haven’t seen that. |

A short timeline of German dialect evolution

History is messy and doesn’t move in a straight line. Nowhere is this more apparent, perhaps, than in the evolution of German dialects. The divide between Low German and High German was shaped gradually by geography, trade, politics and even the printing press.

High German dialects evolved in the upland (southern) regions and underwent the High German consonant shift around 900 CE. This gave rise to Old High German, which later developed into Middle High German during the Middle Ages.

With Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible in the 16th century, a more unified written form (based on an East Central German dialect) began to emerge. By the 19th century, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm and others helped codify Modern Standard German, which became dominant through education and media.

Low German, spoken in the northern lowlands, followed a different path. It began as Old Saxon, developed into Middle Low German and flourished in trade hubs across Northern Europe. However, its influence waned after the 17th century, as High German became the language of power, religion and printing. Today, Low German survives mainly in spoken form, and it’s often viewed as a regional heritage rather than as a standardized language.

Key differences between High vs. Low German

| Feature | High German | Low German |

| Region | South and Central Germany, Austria, Switzerland | Northern Germany |

| Phonology | Affected by consonant shift | Preserves original sounds |

| Status | Standardized and taught | Considered regional dialects |

| Written Standard | Yes (Standard High German) | Largely oral; fewer written norms |

| Usage | Nationwide; formal settings | Local; often familial or cultural |

Cultural and linguistic importance today

Low German: A living dialect

Today, Low German (Plattdeutsch) is mostly spoken in northern parts of Germany and the northeastern Netherlands. Especially in rural communities from Lower Saxony to Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, you can still hear some Platt speakers. Many older generations continue to use it in daily life, and some schools and local media even offer content in Platt to help preserve the tradition.

Interestingly, Low German has also found a second life far from its northern roots. Variants are spoken by Amish and Mennonite communities in the United States, Canada, Mexico and Paraguay. For the people who emigrated from Low German regions to these parts of the world, Low German is a source of cultural pride and its preservation is an important part of German tradition.

What our students of German say

High German: The backbone of Standard German

High German forms the base of Standard German, which is the version used in schools, government institutions and international settings. You’ll hear it on national news, find it in textbooks, and use it when communicating in international or professional contexts. If you want to learn German, this is the version of German you’ll encounter in language schools (unless it’s explicitly stated otherwise).

Today, High German is spoken beyond Germany’s borders — in Austria, much of Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, and parts of eastern France (like Lorraine). While regional accents and dialects still add local flavor, Hochdeutsch remains the unifying language that connects millions of speakers across different countries and cultures.

How different are High German and Low German?

High German and Low German differ significantly in pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar. These differences stem mainly from the High German consonant shift, which Low German did not undergo, making the two sound quite distinct.

Can High German speakers understand Low German?

While some words may be similar, many High German speakers find Low German difficult to understand without prior exposure, as it can sound almost like a separate language rather than a dialect.

Bridging the past and present of German

While High German is more relevant to your language journey than Low German, the evolution of the German language remains fascinating nonetheless. Both dialects are utterly important to the German linguistic heritage and carry centuries of history, identity and regional pride.

High German might be your everyday classroom companion, but Low German gives you a glimpse into Germany’s diverse roots and cultural richness. Exploring both helps you grasp how the language evolved — and how it’s still changing.

At Lingoda, you’ll find teachers from all over the German-speaking world with a deep understanding of regional dialects and how they differ from Standard German. Whether you’re visiting a class in German A1 or German C1, our teachers will make sure that you learn how people actually speak.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

Understanding and using the present progressive (continuous) in English

The present progressive tense, also called the present continuous, is used to talk about actions happening now, temporary situations, and future plans. It’s one of the first English tenses learners study, and one of the most commonly used in everyday conversation. But, it’s also a tense that learners struggle to use accurately.

In this article, you’ll learn how to form the present progressive, when to use it, and how it compares to the present simple. You’ll also see common examples and learn practical tips for using it correctly in real-life situations, from daily routines to professional settings. Whether you’re learning English for work, study, or travel, understanding this tense will help you speak more naturally and confidently.

- What is the present progressive tense?

- When to use the present progressive tense

- How to form the present progressive tense

- Present progressive vs. present simple

- Practical examples and tips for mastering the present progressive

- FAQs

What is the present progressive tense?

The present progressive is an English present tense. It is used to describe actions currently in progress, temporary situations, and future arrangements. We can also use it to talk about situations that are changing and to express annoyance. We form the present progressive like this:

subject + am/is/are + present participle (-ing verb)

It’s very common to contract ‘be’ in the present progressive, especially in speech and informal writing. (I am → I’m; we are → we’re) Here are some examples of the present progressive:

- I’m trying to finish this report.

- You are making too much noise.

- He’s running really quickly.

- We’re just driving home.

- They are learning English.

We don’t tend to use stative verbs in the present progressive. We use the present simple instead.

- I’m understanding. ❌ → I understand. ✅

- He’s believing anything you tell him. ❌ → He believes anything you tell him. ✅

Learn English with Lingoda

How it works

When to use the present progressive tense

Actions happening now

One of the most common uses of the present continuous tense is to talk about actions happening now, either at the moment of speaking or around the time of speaking. These are unfinished actions — they’re in progress.

- What are you doing?

- I’m cooking dinner. ← This most likely refers to what’s happening at exactly the moment of speaking.

- They are renovating their house. ← They may not be doing this at the exact moment of speaking, but the renovation is in progress now.

Temporary situations

We use the present progressive to talk about situations or actions that we see as temporary rather than permanent or habitual.

- She’s staying with her sister this week. (But she normally lives somewhere else.)

- We are working in Paris for the next few months. (But we normally work in Warsaw.)

- I’m going to the gym in the mornings at the moment. (But I normally go at another time of day.)

Future plans

The present progressive can also express future plans or arrangements. These are things in the future that have already been planned or organised.

- We’re having dinner with my parents tomorrow.

- Ingrid is starting a new job next week.

- I’m going to Los Angeles on Sunday.

Changing or developing situations

To talk about situations that are evolving or developing over time, we can also use the present continuous. The implication is that the situation will continue to change as time goes on.

- My children are growing up so quickly!

- The weather is getting better every day.

Repetitive actions with ‘always’

We can also use the present progressive with the adverb ‘always’ to express annoyance at habits or to make complaints. ‘Always’ appears after ‘be’.

- You’re always losing your keys!

- He’s always interrupting me.

What our students of English say

How to form the present progressive tense

Negative sentences

To form negative sentences in the present progressive, we use this structure:

subject + be + not + -ing verb

- I’m not enjoying this film.

- Kate is not feeling well.

- They’re not behaving very well.

Questions

We form yes/no questions in the present continuous like this:

be + subject + -ing verb

- Are you leaving?

- Is he having dinner with us?

We form wh-questions similarly:

wh-word + be + subject + -ing verb

- Where are you going?

- Who is she speaking with?

Present progressive vs. present simple

Here is a comparison table showing some of the main ways the present progressive and present simple are used, with examples.

| Present progressive | Present simple |

| actions happening now or around now I’m having breakfast. Can I call you back?. | regular habits and routines I have breakfast at 7 every morning. |

| temporary actions or situations He’s living in London for the summer. | permanent states or facts He lives in New York. |

| developing or changing situations The sun is rising earlier every day at the moment. | general truths and scientific facts The sun rises in the east. |

| future plans and arrangements We’re going to Berlin tomorrow. | timetables / fixed schedules The train leaves at 8 in the morning. |

Practical examples and tips for mastering the present progressive

One of the best and easiest ways to master the present progressive is to narrate your actions throughout the day.

- I’m washing my face. Now I’m brushing my teeth.

To add more variation, try imagining what other people are doing at that moment or describe images of people (we use continuous tenses to do this in English). Doing this should help you nail the structure.

In professional settings, the present continuous is essential for describing what you’re currently working on, what your plans are, and to describe changes:

- We’re working on the Q3 report.

- Our team is growing rapidly this year.

If you would like to master the present progressive, learn English online with Lingoda. Lingoda’s small-group classes give you plenty of time to practise, and you’ll be guided by a native-level teacher, who can provide useful, real-life examples and help you sound more natural.

What is an example with present progressive?

“I am listening to a podcast.” This is an example of a present progressive sentence.

What 3 things do you need to form the present progressive?

To form the present progressive, you need a subject, the auxiliary verb ‘be’ in the present tense, and a present participle (-ing verb).

What is the rule for present progressive?

Generally, we don’t use stative verbs in the present progressive. We use action verbs.

Final thoughts on the present continuous

The present progressive helps you talk about what’s happening now, what’s changing, and what’s planned. Mastering it will help you make distinctions between temporary and permanent situations and future plans versus things you’d simply like to happen.

The best way to learn English, including practising the present progressive in real conversations, try online language learning with Lingoda. Classes are available 24/7, so you can study when it suits you. Thanks to Lingoda’s small class sizes, you’ll learn to use the present progressive and speak with confidence from day one.

Learn English with Lingoda

How it works

When to use ‘als’, ‘wenn’ or ‘wann’ in German

Choosing between als or wenn in German can be tricky. In English, we often use a single word (“when”) that can translate to both conjunctions. But German makes a finer distinction. Whether you use als or wenn depends on whether you’re talking about the past or the future, or a single event, or a repeated action, or a condition.

In this guide, you’ll learn how temporal clauses work in German grammar — which includes a discussion of how to correctly apply als and wenn. We’ll review some illustrative examples to show you the difference and get you ready to form your own temporal clauses.

- Understanding temporal clauses in German grammar

- Using als: Referring to single events in the past

- Using wenn: For repeated actions, future events and conditions

- Using wann: Asking or referring to a point in time

- Als vs. wenn: Making the right choice

- Wann vs. wenn: Timing vs. condition

- FAQs

Understanding temporal clauses in German grammar

What are temporal clauses?

Temporal clauses (Temporalsätze) are subordinate clauses that provide information about when an action or event in the main clause takes place. They are introduced by conjunctions like als or wenn and follow standard subordinate clause word order in German.

Temporal clauses are used to talk about sequences, repetitions, or durations of actions and events in the past, present or future.

Why word order matters in German clauses

In German, the word order in main clauses and subordinate clauses differs primarily in the verb’s position.

In main clauses, the conjugated verb is always in the second position. The subject can appear in the first or third position, depending on the word order.

In subordinate clauses, the conjugated verb is placed at the end of the clause. In the case of compound tenses, this means that the participle comes before the auxiliary verb (e.g. haben or sein), and the auxiliary verb is placed at the very end of the clause.

Temporal conjunctions like als or wenn introduce subordinate clauses and take the first position, providing information about when the action takes place:

- Als ich ankam, war es schon zu spät. (When I arrived, it was already too late.)

- Wenn ich losfahre, rufe ich dich an. (When I leave, I’ll call you.)

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

Using ‘als’: Referring to single events in the past

The conjunction als is used to talk about a single event that happened in the past. It indicates that something occurred only once, not repeatedly:

- Als wir uns trafen, war es 18 Uhr. (When we met, it was 6 p.m.)

Using ‘wenn’: For repeated actions, future events and conditions

The conjunction wenn is quite versatile. It refers to repeated actions in the past, events in the present and future and conditions.

Repeated events in the past

If an event or situation happened more than once in the past, the conjunction wenn is used:

- Wenn es im Sommer heiß war, gingen wir jeden Tag ein Eis holen. (When it was hot in the summer, we went out for ice cream every day.)

Present, future and conditional sentences

Wenn applies to present and future situations, too. This is true regardless of how often they occur:

- Wenn ich Kaffee trinke, fühle ich mich wacher. (When I drink coffee, I feel more awake.)

- Wenn wir in Rom sind, werden wir das Kolosseum besuchen. (When we are in Rome, we’ll visit the Colosseum.)

Wenn can also be used to form conditional sentences in German, much like “if” in English:

- Wenn es morgen regnet, besuchen wir ein Museum. (If it rains tomorrow, we’ll visit a museum.)

Comparing ‘wenn’ to ‘falls’ (if/in case)

Wenn and falls both serve to introduce a condition in German, but they differ slightly in tone and nuance.

Wenn implies a real, likely or repeated event and usually translates to “if” in English:

- Wenn die Sonne scheint, gehen wir spazieren. (If the sun shines, we go for a walk.)

Falls, on the other hand, sounds more hypothetical or cautious and is often considered more formal. It’s closer in meaning to “in case” in English and typically refers to conditions that are less likely and/or not repeated:

- Falls ihr früher zu Hause seid, können wir zusammen essen. (In case you get home earlier, we can eat together.)

What our students of German say

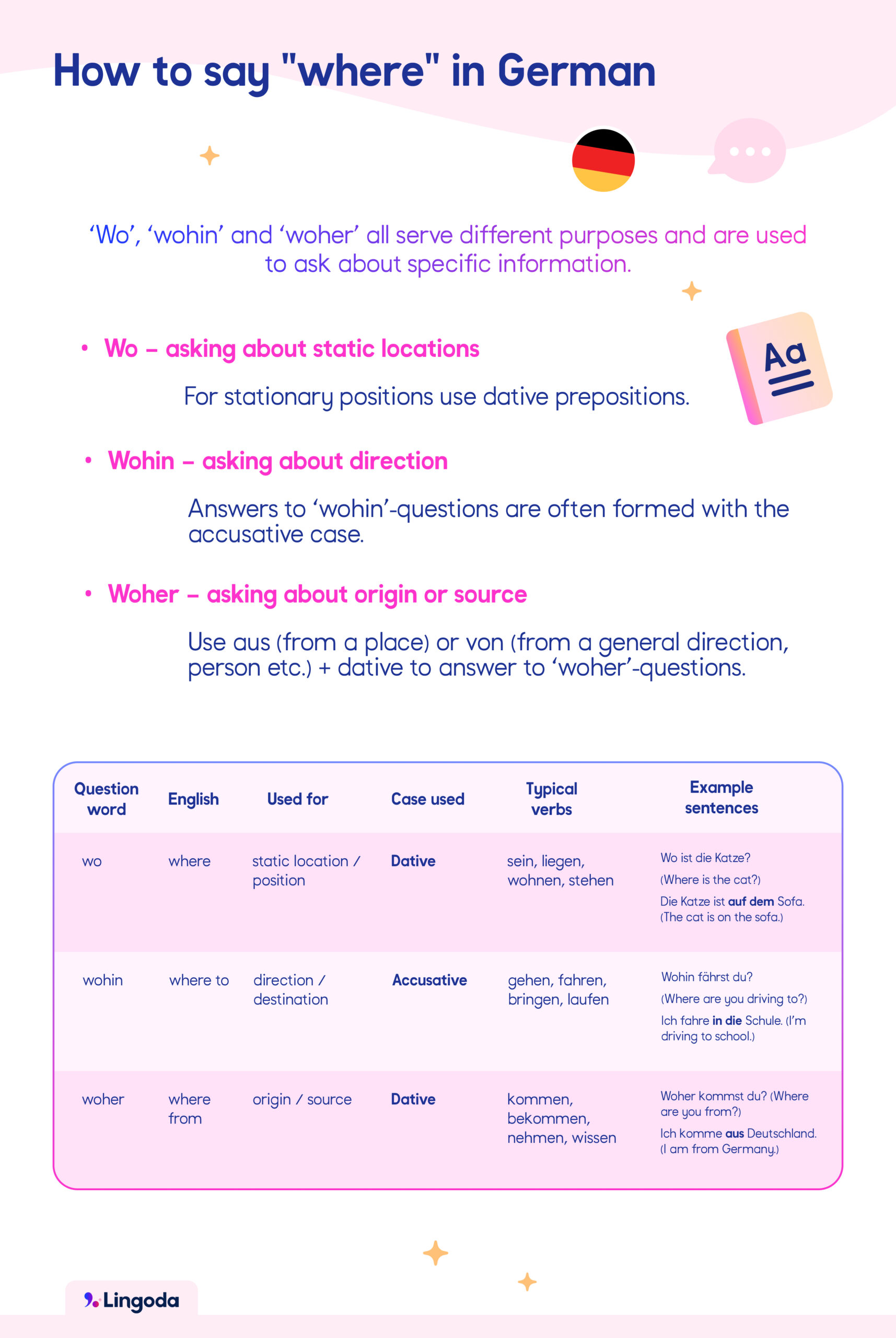

Using ‘wann’: Asking or referring to a point in time

Direct questions with ‘wann’

If you want to ask when something happens, use wann, which translates to “when” in English.

In direct questions, wann typically comes at the beginning of the sentence:

- Wann sehen wir uns? (When will we see each other?)

Indirect questions and subordinate clauses

Wann is also used in subordinate clauses to introduce indirect questions. These clauses depend on a main clause and follow the standard word order in which the verb is placed at the end:

- Ich weiß nicht, wann sie kommt. (I don’t know when she’s coming.)

The key difference between direct and indirect questions is the word order. In indirect questions, the verb moves to the end of the clause.

‘Als’ vs. ‘wenn’: Making the right choice

Deciding whether to use als or wenn can be challenging. Even though both translate to “when” in English, they’re not interchangeable in German.

The main difference between these temporal conjunctions lies in tense and frequency:

- Als is for single events in the past.

- Wenn is for repeated events, conditions and any present or future events — regardless of how often they occur.

One-time vs. repeated events

| Tense | Single event | Repeated event |

| Past | als | wenn |

| Present | wenn | wenn |

| Future | wenn | wenn |

‘Wann’ vs. ‘wenn’: Timing vs. condition

Wann and wenn may look and sound similar, but they serve different purposes in German.

Wann is used to ask when something happens. In direct questions, it appears at the beginning of the sentence; in indirect questions, it functions as part of a subordinate clause.

Wenn expresses a condition, similar to “if” in English. It’s not used in questions and always introduces a subordinate clause that describes the condition for the main clause.

Let’s see some examples:

- Wann fahren wir in den Urlaub? (When do we go on vacation?)

Here we are asking about the specific point in time in which we are going on vacation. Contrast this example with the following:

- Wenn ich müde bin, gehe ich früher ins Bett. (If I’m tired, I go to bed earlier.)

This sentence isn’t a question. The action in the main clause depends on the condition stated in the subordinate clause.

When do you use als vs. wenn in German?

Als is used for single events in the past. Wenn applies to repeated events, present or future actions, and conditions.

Is wenn used to refer to the past or the future?

Wenn is used for both the past and the future. In the past, it refers to repeated events, while in the future, it introduces any event or condition, regardless of how often they occur.

Key Takeaways on ‘als’, ‘wenn’ and ‘wann’

Mastering the difference between als, wenn and wann is key for forming accurate temporal and conditional sentences in German. Use als for single events in the past; wenn for repeated actions, present or future events and conditions; and wann to ask when something happens, either directly or indirectly.

Before focusing on these conjunctions, make sure you understand how to talk about the past in German and build a solid foundation in tense usage and sentence structure.To put these concepts into practice in real conversations, try Lingoda’s small group classes led by native-level teachers. Find your level, from German A1 to German C1, and start learning at your own pace.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

13 long German words you’ll actually use (and one you’ll probably never say)

Let’s face it: German words have a reputation for being quite long. To non-German speakers, they can look less like vocabulary and more like a keyboard malfunction. But a good number of these impressively lengthy words are not mere linguistic curiosities. They’re alive and well in everyday German usage.

In this guide, we’ll explore 13 of the longest and most difficult German words you might actually use in real life. Plus, we’ll throw in one absurdly long outlier that exists purely to break records. Along the way, we’ll break down why German words get so long in the first place and how you can learn them without melting your brain. Spoiler: there’s logic behind the chaos.

Ready to surprise yourself with how usable some of the longest German words really are? Let’s dive in.

- Why are German words so long?

- 13 long German words you’ll actually use

- What’s the longest German word ever?

- How to learn long German words without getting overwhelmed

- FAQs

Why are German words so long?

German isn’t trying to scare you — it’s just playing by different rules.

The reason long German words exist at all comes down to one glorious concept: compound words. Instead of borrowing terms from other languages, German often takes two (or three, or four) existing words and glues them together into one mega-word that can seem quite literal in its translation.

At the core of this linguistic phenomenon are morphemes — the smallest units of meaning. Put simply, German loves combining morphemes. Add a prefix here, a suffix there, stack up a few nouns in between, and voilà: Krankenhausverwaltungssystem (hospital administration system) is born.

German grammar actually encourages this. There’s no real limit to how many nouns you can stack, as long as the meaning stays clear. It reflects a very German style of efficiency. In government, engineering and other professions where precision is king, compound words help communicate highly specific ideas without ambiguity.

So, yes, the words get long — but they’re not random. They’re custom-built for clarity.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

13 long German words you’ll actually use

1. ‘Kraftfahrzeughaftpflichtversicherung’ (car liability insurance)

- Definition: Car liability insurance

- Breakdown: Kraft (power) + Fahrzeug (vehicle) + Haftpflicht (liability) + Versicherung (insurance)

- Example: Ich brauche eine neue Kraftfahrzeughaftpflichtversicherung für mein Auto.

- Context: Bureaucratic/legal

- Pronunciation tip: Break it into eight parts: Kraft-fahr-zeug-haft-pflicht-ver-siche-rung

2. ‘Rechtsschutzversicherungsgesellschaften’ (legal protection insurance companies)

- Definition: Legal protection insurance companies

- Breakdown: Recht (law) + Schutz (protection) + Versicherung (insurance) + Gesellschaften (companies)

- Example: Rechtsschutzversicherungsgesellschaften bieten Hilfe bei juristischen Streitfällen.

- Context: Legal/insurance

- Note: Pluralization adds even more length. Take a deep breath before attempting this one.

3. ‘Aufenthaltsgenehmigung’ (residence permit)

- Definition: Residence permit

- Breakdown: Aufenthalt (residency/stay) + Genehmigung (permission)

- Example: Ich habe endlich meine Aufenthaltsgenehmigung bekommen!

- Context: Immigration/bureaucracy

- Pronunciation tip: Emphasize Auf-ent-halts to keep rhythm.

4. ‘Geschwindigkeitsbegrenzung’ (speed limit)

- Definition: Speed limit

- Breakdown: Geschwindigkeit (speed) + Begrenzung (limitation)

- Example: Die Geschwindigkeitsbegrenzung auf der Autobahn beträgt 130 km/h.

- Context: Road regulations

5. ‘Unfallversicherungsgesetz’ (accident insurance law)

- Definition: Accident insurance law

- Breakdown: Unfall (accident) + Versicherung (insurance) + Gesetz (law)

- Example: Das Unfallversicherungsgesetz schützt Arbeitnehmer im Falle eines Arbeitsunfalls.

- Context: Legal/workplace safety

6. ‘Hausratsversicherung’ (home contents insurance)

- Definition: Home contents insurance

- Breakdown: Hausrat (household contents) + Versicherung (insurance)

- Example: Meine Hausratsversicherung deckt auch Wasserschäden ab.

- Context: Domestic/insurance

7. ‘Lieferungsbestätigung’ (delivery confirmation)

- Definition: Delivery confirmation

- Breakdown: Lieferung (delivery) + Bestätigung (confirmation)

- Example: Bitte senden Sie uns eine Lieferungsbestätigung per E-Mail.

- Context: Business/logistics

8. ‘Gesundheitsschutzmaßnahmen’ (health protection measures)

- Definition: Health protection measures

- Breakdown: Gesundheit (health) + Schutz (protection) + Maßnahmen (measures)

- Example: Die Regierung hat neue Gesundheitsschutzmaßnahmen eingeführt.

- Context: Public health/government policy

What our students of German say

9. ‘Arbeitsunfähigkeitsbescheinigung’ (sick leave certificate)

- Definition: Sick leave certificate

- Breakdown: Arbeitsunfähigkeit (inability to work) + Bescheinigung (certificate)

- Example: Der Arzt hat mir eine Arbeitsunfähigkeitsbescheinigung ausgestellt.

- Context: Workplace/medical

- Pronunciation tip: Tackle it in chunks: Ar-beits-un-fä-hig-keits-be-schei-ni-gung.

10. ‘Lebensmittelunverträglichkeit’ (food intolerance)

- Definition: Food intolerance

- Breakdown: Lebensmittel (food) + Unverträglichkeit (intolerance)

- Example: Ich habe eine Lebensmittelunverträglichkeit gegenüber Laktose.

- Context: Medical/dietary

11. ‘Personalausweisnummer’ (ID card number)

- Definition: ID card number

- Breakdown: Personalausweis (ID card) + Nummer (number)

- Example: Bitte geben Sie Ihre Personalausweisnummer an.

- Context: Administrative/identification

12. ‘Straßenverkehrsordnung’ (road traffic regulations)

- Definition: Road traffic regulations

- Breakdown: Straße (street) + Verkehr (traffic) + Ordnung (rules/regulations)

- Example: Die Straßenverkehrsordnung regelt das Verhalten im Straßenverkehr.

- Context: Legal/road safety

13. ‘Versicherungsgesellschaft’ (insurance company)

- Definition: Insurance company

- Breakdown: Versicherung (insurance) + Gesellschaft (company)

- Example: Die Versicherungsgesellschaft hat den Schaden übernommen.

- Context: Business/legal

What’s the longest German word ever?

Ah, yes, the legend itself:

Rindfleischetikettierungsüberwachungsaufgabenübertragungsgesetz (63 letters long — yes, we counted.)

Definition: Beef labeling supervision duties delegation law

Breakdown:

- Rindfleisch – beef

- Etikettierung – labeling

- Überwachung – supervision

- Aufgaben – duties

- Übertragung – transfer/delegation

- Gesetz – law

This Frankenstein of a noun was coined in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern for a very specific piece of legislation about the authority responsible for monitoring beef labeling. Bureaucracy, meet linguistic maximalism.

Don’t worry, though. This one is definitely considered advanced German vocabulary, and as such it’s not necessary to learn right away (or ever, if we’re being honest). Though the law itself was repealed in 2013, the unwieldy word it spawned lives on in memes, textbooks and cocktail party trivia. Why? Because it’s a perfect example of how German can technically build words with no upper limit in terms of length — as long as the logic holds.

How to learn long German words without getting overwhelmed

Long German words aren’t a memory test — they’re more like puzzles. And once you know how to approach them, they become a lot less intimidating. Here’s a simple, repeatable strategy:

- Break it into parts. Start by slicing the word into smaller chunks. Look for familiar roots: Versicherung, Gesetz, Nummer. These are your anchor points.

- Identify the root word. What’s the core idea? In Hausratsversicherung, the root is Versicherung (insurance). Everything before it just makes it more specific.

- Use context. Don’t try to learn words in a vacuum. Study and use them in sentences, emails, documents and more. Real use gives real meaning.

- Repetition beats memorization. You don’t need a flashcard for Geschwindigkeitsbegrenzung — you just need to see it on enough highway signs.

That’s where Lingoda can help. In live, structured classes with native-level teachers, you’ll hear words in context and practice them in conversation until they feel natural.

What is the longest German word ever used?

Rindfleischetikettierungsüberwachungsaufgabenübertragungsgesetz (63 letters) — a former legal term.

Are long German words common in everyday conversation?

Some are, especially in admin or work contexts. But monster-length words are usually avoided in casual speech.

Long words, shortcuts to language mastery

Long German words aren’t here to scare you. Many of them are practical, everyday terms, especially in work, legal and health contexts. When you break them down and see them in use, they stop being intimidating.

Remember: long words are often just short ideas stacked together. Learn them in pieces, use them in context, and practice regularly. Set yourself a “word of the week” challenge: pick one chunky German word, learn it, use it in sentences and try it out loud. Lingoda’s live classes are perfect for this kind of real-time, real-language learning.Tackle them one at a time, and soon you’ll be casually dropping Geschwindigkeitsbegrenzung into conversations like it’s no big deal. Because for you, it won’t be.

Learn German with Lingoda

How it works

10 cultural mistakes expats make in their first month in Germany

Ever asked a German local about the quirks of daily life? Chances are, they’ll say there’s nothing unusual at all. But what feels perfectly normal to a German can be completely bewildering to someone from abroad.

For expats who have recently landed in Germany, these differences often add up to a general sense of culture shock. The good news? Many have already attempted the move to Germany and made mistakes that you can learn from. By taking their stories to heart, you can ensure a smoother experience for yourself.

In this article, we’ll help you prepare for new situations and cultural surprises. We’ll also discuss some measures you can take to get a headstart on your life in Germany.

- Everyday habits that can make life in Germany more challenging

- Adapting to a new professional culture

- Habits that quietly hold back your integration

- Social norms that are easy to miss (but matter)

Everyday habits that can make life in Germany more challenging

Moving to Germany comes with its fair share of challenges — from looking for a flat to finding new friends and a job. But there are ways to make it all a little easier. And just as important as what you should do is what you shouldn’t.

1. Assuming English will be enough

It really depends on where you move to in Germany. In big cities like Berlin, many offices operate in English and the barista at the nearby coffee shop will probably switch to English if you struggle to say, “Ich hätte gerne einen Kaffee” (“I’d like a coffee”).

But don’t be fooled. Getting by in English is not the same as fully integrating. German is still the language of everyday life in cities like Frankfurt and Berlin, and it’s easy to feel isolated if you can’t connect to others properly. As André Klein, author of the Learn German with Stories series, puts it, “Language isn’t just a tool for communication — it’s a key to understanding how people think, live and connect.”

That doesn’t mean you need to become fluent in your first weeks or months, though. Take it easy, start with key phrases and use every opportunity you get to practice your German skills. You’ll see it pays off with time.

2. Delaying your Anmeldung appointment

This is a big one among expats: the Anmeldung. This residency registration is your golden ticket to life in Germany. It unlocks access to essential services like health insurance, bank accounts, mobile plans and basically everything else you need in everyday life.

As there can be long waiting lists in some regions in Germany, it’s best to book your Anmeldung appointment online before you arrive — weeks in advance, if possible.

3. Missing the subtle rules of public spaces

German public spaces adhere to subtle — but strict — social codes. Here are the most important ones to look out for:

- Respect the quiet hours: No noise is allowed in public areas between certain times of the day. Depending on your region, quiet hours can start at 10 p.m. and last until 7 a.m.

- Don’t walk inside bike lanes. You’ll likely be called out for it — and rightfully so, as it’s also dangerous. These lanes often run alongside sidewalks but are clearly marked and strictly respected.

- When using the escalators, always stand on the right side so people walking up can pass you on the left.

- Sorting trash is a civic duty in Germany. Not following the correct sorting procedures for your region could make you an unpopular neighbor.

The best strategy? Watch and learn. Subtle cultural cues are everywhere — just follow the locals’ lead.

Adapting to a new professional culture

Starting a new job is always exciting and a little stressful. Doing it in another country is even more so. Germany’s professional culture has some (often unspoken) rules that you should try to learn and follow.

Here are some common mistakes and experiences expats face in their first days in the office.

4. Jumping into informality too quickly at work

There are two ways to address someone in German. You can either use du for informal situations or Sie for formal ones.

Especially in business culture, always default to Sie and use your colleagues’ last names until they “offer” the du. Once you’re on more familiar terms, you may get the go-ahead to switch to first names.

5. Learning the value of directness in German conversations

Depending on the cultural norms you’re used to, German speakers can seem quite harsh in their communications. But this is by design, as directness is highly valued in German culture and often prioritized over the more verbose forms of politeness.

It’s important to remember that directness does not always equal rudeness. Feedback is meant to be clear, honest and actionable — certainly not personal. If something feels off, it’s best to ask questions honestly. You may even be appreciated for showing initiative.

6. Overworking in a culture that values balance

Working late hours won’t prove your dedication or willingness to work hard. On the contrary, it might suggest poor time management.

As an employee, try to focus on the quality of your work (which doesn’t give you license to miss deadlines). Time off is also highly respected in Germany because it gives employees necessary time to recharge.

Habits that quietly hold back your integration

While it’s hard to tell exactly when someone is “fully integrated,” it’s painfully easy to tell when they’re not. In the beginning, the following habits are most likely the culprits.

7. Skipping out on language or integration courses

You might have nailed the basics within your first month — found a flat, landed a job — but still feel like an outsider. This is why a support system is important. A language or integration course offers more than just classroom time. It helps you feel more confident and connected with the place you’re living in.

If you’re looking for affordable or free options, check out the offers at the Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF; the federal office for migration and refugees) or the local Volkshochschule (adult education center).

8. Expecting services to work like they do at home

Maybe fast digital processes and personalized customer service were the norm in your country of origin. If that’s the case, adjusting to strict opening hours, limited flexibility and bureaucratic paperwork can be challenging.

But these are some of the hurdles you’ll face when attempting to access important services like health insurance or work permits. Although the adjustment can be frustrating at first, try to accept the local norms. It will make it easier for you to adapt to the German system.

Social norms that are easy to miss (but matter)

A quick internet search will reveal that there are many expats in Germany who struggle with making connections. Germans have earned a reputation for being inaccessible and cold. But is this really true?

In reality, social connections in Germany just happen a little differently. Here are a couple of early mistakes to avoid on your way to making friends.

9. Expecting friendly chit-chat right away

In Germany, directness isn’t just for the boardroom — it extends to social life, too. Being overly chatty can be seen as needy, which is why a lot of people might seem reserved to you at first. But that doesn’t mean they’re unfriendly.

German friendships are slow to build but incredibly solid once they’re established. Give it time, because the following quote rings true: “German friendships are like oak trees — slow to grow, but strong and lasting once rooted.” (Adam Fletcher, author of How to Be German).

10. Overlooking how important punctuality really is

Being ten minutes late for a work call is unacceptable. In a society where punctuality is the Holy Grail, people will think you’re not valuing their time if you don’t make an effort to be punctual.

Aim to arrive five minutes early. It’s a small habit that speaks volumes about your reliability.

Start with understanding, end with belonging

Your first month in Germany will probably feel like a cultural crash course — and that’s perfectly fine. Even well-prepared professionals can make missteps. Try to be patient with yourself, and remember you don’t need to know it all in the beginning.

Join local communities. Sign up for a language course. Get involved in neighborhood events. Every small step will help you feel more at home and turn new surroundings into familiar ground.

Begin your personal language journey

- Courses tailored to your learning needs

- Qualified native-level teachers

- Expert-designed curriculum

- Live classes with small group sizes

‘Avoir’ conjugation: How to use this essential French verb

Mastering avoir conjugation is essential for anyone learning French.

As the second most common verb in French after être (to be), avoir (to have) serves important functions in everyday communication. It notably helps to express possession, state a person’s age, and convey a wide range of emotions and physical states. Beyond these fundamental uses, avoir also functions as an auxiliary verb to form compound tenses like the passé composé.

This comprehensive guide will walk you through the conjugation of avoir in all major tenses, including present, past, future and conditional forms, along with the subjunctive and the imperative. You’ll also discover how to use avoir in some common idiomatic expressions that can help your French sound more fluent.

- Present tense conjugation of avoir

- ‘Avoir’ in the past: ‘Passé composé’ and beyond

- Future and conditional tenses with avoir

- Subjunctive and imperative forms of avoir

- Common idiomatic expressions using avoir

Present tense conjugation of ‘avoir’

Here’s the conjugation table for the verb avoir in the present simple tense, with some examples for each person:

| French | English | Example |

| J’ai | I have | J’ai une voiture. (I have a car.) |

| Tu as | You have | Tu as une voiture. |

| Il/Elle/On a | He/She/It has | Il a une voiture. |

| Nous avons | We have | Nous avons une voiture. |

| Vous avez | You have | Vous avez une voiture. |

| Ils/Elles ont | They have | Elles ont une voiture. |

‘Avoir’ in the past: ‘Passé composé’ and beyond

To speak French fluently, you also need to master other French tenses.

Let’s start with past tenses: the compound past, the imperfect and the past perfect. Below, you’ll find everything you need to know about the conjugation of the verb avoir in these past tenses.

‘Passé composé’: ‘Avoir’ as an auxiliary verb

The compound past tense is used to describe actions that were completed in the past.

It’s formed with the present tense of an auxiliary verb (avoir or être), followed by the past participle.

The past participle is formed by adding specific endings to the verb stem:

- “é” with verbs ending in “-er”;

- “i” with most verbs ending in “-ir”;

- “u” with regular verbs ending in “-re”;

- other endings including “-u”, “-is” and “-it” with irregular verbs.

Here’s a summary table with examples:

| Formation | Examples |

| J’ai [+ past participle] | J’ai beaucoup mangé. (I ate a lot.) |

| Tu as [+ past participle] | Tu as beaucoup mangé. |

| Il/Elle/On a [+ past participle] | Il a beaucoup mangé. |

| Nous avons [+ past participle] | Nous avons beaucoup mangé. |

| Vous avez [+ past participle] | Vous avez beaucoup mangé. |

| Ils/Elles ont [+ past participle] | Elles ont beaucoup mangé. |

The past participle of the verb avoir is eu. For example:

- Elle a eu des cadeaux pour son anniversaire. (She received gifts for her birthday.)

‘Imparfait’: Describing ongoing or repeated past actions

The imperfect tense is used to describe habitual, background or ongoing past actions.

It’s formed by adding imperfect endings (-ais, -ait…) to the verb stem (av-).

| French | English | Examples |

| J’avais | I had | J’avais un chien. (I had a dog.) |

| Tu avais | You had | Tu avais un chien. |

| Il/Elle/On avait | He/She/It had | Elle avait un chien. |

| Nous avions | We had | Nous avions un chien. |

| Vous aviez | You had | Vous aviez un chien. |

| Ils/Elles avaient | They had | Ils avaient un chien. |

‘Plus-que-parfait’: The ‘past of the past’

The past perfect is used to express an action that happened before another past action.

It’s formed with the imperfect form of avoir, followed by the past participle of the verb.

| Formation | Examples |

| J’avais [+ past participle] | J’avais eu de la chance. (I had been lucky.) |

| Tu avais [+ past participle] | Tu avais eu de la chance. |

| Il/Elle/On avait [+ past participle] | Elle avait eu de la chance. |

| Nous avions [+ past participle] | Nous avions eu de la chance. |

| Vous aviez [+ past participle] | Vous aviez eu de la chance. |

| Ils/Elles avaient [+ past participle] | Ils avaient eu de la chance. |

Future and conditional tenses with ‘avoir’

Now that you’ve mastered the conjugation of avoir in the various past tenses, let’s examine two other essential verb tenses in French: the future and the conditional.

What our students of French say

‘Futur simple’: Expressing certainty or scheduled events

The simple future is used to describe events that will happen.

It’s formed with the future stem of the verb avoir (aur-), followed by future endings.

| French | English | Examples |

| J’aurai | I will have | J’aurai du travail en septembre. (I will have work in September.) |

| Tu auras | You will have | Tu auras du travail en septembre. |

| Il/Elle/On aura | He/She/It will have | Elle aura du travail en septembre. |

| Nous aurons | We will have | Nous aurons du travail en septembre. |

| Vous aurez | You will have | Vous aurez du travail en septembre. |

| Ils/Elles auront | They will have | Ils auront du travail en septembre. |

‘Conditionnel présent’: Expressing politeness or hypotheticals

The present conditional tense is used to describe events that would happen in certain conditions.

It’s formed with the future stem of the verb avoir (aur-), followed by imperfect endings.

| French | English | Examples |

| J’aurais | I would have | J’aurais besoin d’aide. (I would need some help.) |

| Tu aurais | You would have | Tu aurais besoin d’aide. |

| Il/Elle/On aurait | He/She/It would have | Elle aurait besoin d’aide. |

| Nous aurions | We would have | Nous aurions besoin d’aide. |

| Vous auriez | You would have | Vous auriez besoin d’aide. |

| Ils/Elles auraient | They would have | Ils auraient besoin d’aide. |

Subjunctive and imperative forms of ‘avoir’

Let’s now examine how avoir is used in the present subjunctive and imperative forms.

Learn French with Lingoda

How it works

‘Subjonctif présent’: Expressing doubt, emotion or necessity

The present subjunctive is used after expressions of doubt, emotion or obligation. For instance, you’ll often find it in sentences starting with “Je doute que”, “J’aimerais que” or “Il faut que”.

It’s formed with the irregular subjunctive stems of the verb avoir (ai- and ay-), followed by subjunctive endings.

| Formation | Examples |

| Que j’aie | Il n’est pas certain que j’aie reçu la lettre. (It is not certain that I received the letter.) |

| Que tu aies | Il n’est pas certain que tu aies reçu la lettre. |

| Qu’il/elle/on ait | Il n’est pas certain qu’elle ait reçu la lettre. |

| Que nous ayons | Il n’est pas certain que nous ayons reçu la lettre. |

| Que vous ayez | Il n’est pas certain que vous ayez reçu la lettre. |

| Qu’ils/elles aient | Il n’est pas certain qu’ils aient reçu la lettre. |

‘Impératif’: Giving direct commands

The imperative form is used to express direct orders, instructions or encouragement. As imperative commands are always directed to someone, this form is only used with the French pronouns for “you” (singular and plural) and “we” (in which case the speaker is included in the group receiving the command).

Here’s a table with examples to help you remember how it’s formed:

| Formation | Examples |

| Singular you: aie | Aie confiance en toi, tu peux le faire ! (Have confidence in yourself, you can do it!) |

| We: ayons | Ayons confiance en nous, nous pouvons le faire ! |

| Plural you: ayez | N’ayez crainte, tout se passera bien. (Have no fear, everything will be fine.) |

Common idiomatic expressions using ‘avoir’

First, let’s remember that the verb avoir is commonly used for the following purposes:

- To express possession.

Example: J’ai deux voitures. (I have two cars.)

- To state a person’s age.

Example: J’ai 25 ans. (I am 25 years old.) - In two common expressions: il y a (there is) and il n’y a pas (there is not).

In French, idiomatic expressions using the verb avoir are also very common in everyday language. Idiomatic expressions often don’t translate literally, and context may be necessary to understand their idiomatic usage. It’s a great idea to memorize these!

Here are some examples of common expressions using the verb avoir:

- Avoir faim (to be hungry)

- Ex.: J’ai eu faim toute la journée. (I was hungry all day.)

- Avoir peur ( to be afraid)

- Ex.: N’aie pas peur, tout ira bien. (Don’t be afraid, everything will be fine.)

- Avoir raison (to be right)

- Ex.: Vous avez eu raison de refuser. (You were right to refuse.)

- Avoir sommeil (to be sleepy)

- Ex.: J’ai terriblement sommeil. (I am terribly sleepy.)

- Avoir besoin de (to need)

- Ex.: J’ai besoin de me reposer. (I need to rest.)

- Avoir l’air (to seem)

- Ex.: Il a l’air très fatigué. (He seems very tired.)

- Avoir du mal à (to have difficulty)

- Ex.: J’ai du mal à respirer. (I have difficulty breathing.)

The verb avoir is also used in more metaphorical idiomatic expressions:

- Avoir la pêche (to be happy; literally, “to have the peach”)

- Ex.: J’ai la pêche dès que je te vois ! (I feel happy as soon as I see you!)

- Avoir le cafard (to feel sad; literally, “to have the cockroach”)

- Ex.: Elle a le cafard depuis qu’il est parti. (She has been feeling sad since he left.)

- Avoir du pain sur la planche (to have a lot to do; literally, “to have bread on the board”)

- Ex.: C’est chargé en ce moment : j’ai du pain sur la planche ! (It’s busy right now: I have a lot to do!)

- Avoir le bras long (to be influential; literally, “to have a long arm”)

- Ex.: Attention, nous avons le bras long ! (Be careful, we are influential!)

There are many other French idiomatic expressions with avoir. The good news is that they are fun to learn!

Your next step: Mastering ‘avoir’ and beyond

Mastering the avoir conjugation is a fundamental step in learning French. As we’ve seen, avoir is essential for expressing possession, forming compound tenses and creating idiomatic expressions that can help your French sound more fluent.

With Lingoda’s online French grammar lessons, you can learn from certified and native-level teachers who’ll help you practice essential verbs like avoir and être in live, interactive sessions.

Learn French with Lingoda

How it works

Design, team spirit and a dash of bravery: An interview with Bruna Monte, Marketing Designer at Lingoda

Bruna’s a marketing designer at Lingoda and a big fan of bold ideas. She’s all about turning creative concepts into real campaigns, whether it’s featuring students from around the world or testing fun new formats on social. In this interview, she shares why bravery matters, how her team helps her push boundaries, and why good translations need a human touch. Plus, the one desk item she didn’t invite: her cat. Get a peek into Bruna’s world of design, teamwork, and curiosity!

Like what we’re about? You might just be our next teammate so check our career page!

Thanks for making time for us, Bruna! You are a marketing designer at Lingoda – What first drew you to design and what keeps you passionate about it today?

I used to play around with design tools for fun when I was younger, and during my Communication Studies bachelor, I found out I could actually work with design for a living. It was so fun that I couldn’t see that as work in the beginning. What makes me passionate about design today is how much everything changes all the time, with AI, new tools, new styles… I feel like today, everything is possible in Design, and that’s super exciting.

Can you walk us through a project you’re especially proud of? What made it special?

I’m really proud of the New Year campaign of 2023/2024 at Lingoda. I supported the art direction and production of the visuals for the online marketing campaign. It was special because we brought real Lingoda students to Berlin for a photo and video shoot, we got to spotlight them and cheer on their wins. In the campaign, each student shared what their biggest language win was in the language they were learning. For example, one American student had studied French with Lingoda and was able to move to France to work in a Michelin-starred restaurant, turning a language goal into a life-changing career move.

What’s the most unusual or unexpected thing you’ve learned while working at Lingoda?

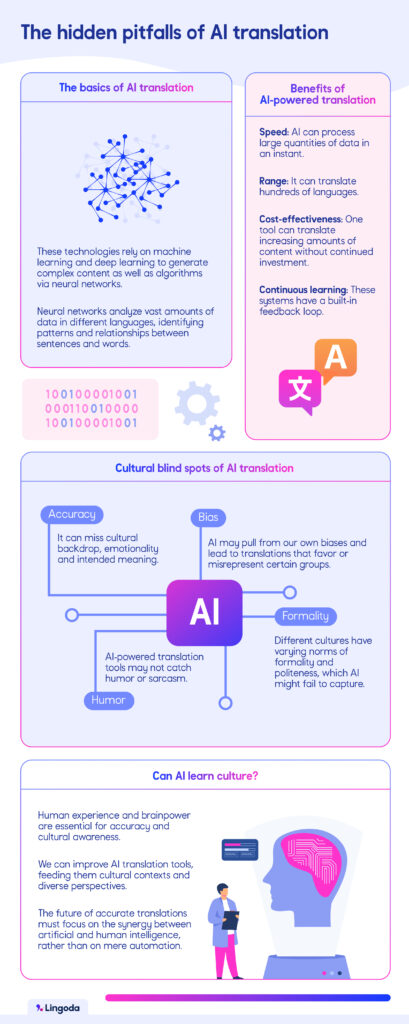

An unusual thing I learnt is that translations are not a simple thing. We don’t just rely on AI or Google Translate for translating our marketing campaigns; we need real people to translate and proofread. This is essential to keep the brand tone of voice and make sure it really resonates with students. It needs to feel personal, because it is.

Looking at our five company values, which one are you connecting to the most? Can you explain why?

I connect most with “Be brave.” As creative people, we are constantly challenged to think outside the box and try new things, and for that, we need to speak up and collaborate as a team.

What’s one thing you’ve learned from your teammates that changed the way you work?

My teammates boosted my confidence at work by creating a supportive environment where we encourage each other to try new things even if they fail – that’s ok, we learn from our failures. For example, on Social Media, we are currently in an exploring phase – testing new formats, new ways of communicating, and we can let our creativity run wild without much fear about whether it works or not. When you don’t restrain where your mind can go, the odds of getting to something really creative and interesting are much higher.

What item is never missing on your desk?

Post-its, a cup of coffee and my cat (he’s uninvited though!)

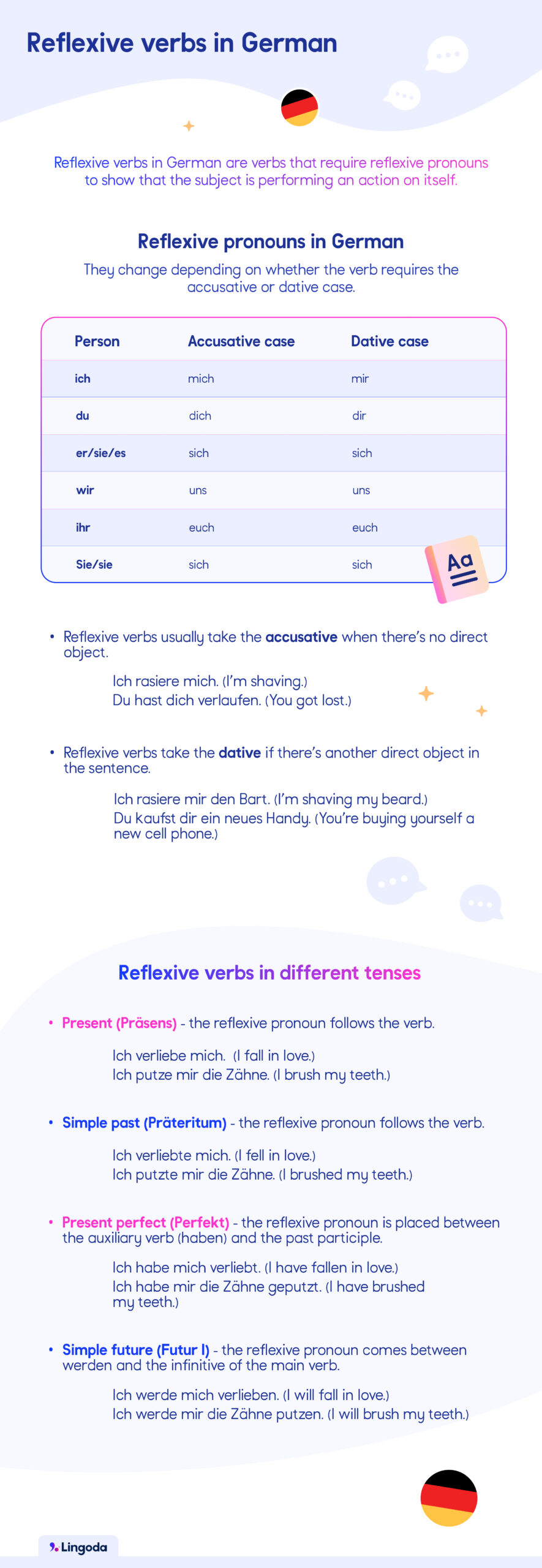

Reflexive verbs in German: How to use, conjugate and understand them

Want to talk about your daily routine, feelings or thoughts in German? You’ll need reflexive verbs.

Brushing your teeth, getting dressed, introducing yourself: these are all situations that demand reflexive verbs in German. You’ll come across these verbs far more often than in English, so it’s worth understanding how they work.

In this article, you’ll learn how reflexive verbs are formed, when to use the accusative or dative case and how to combine a reflexive verb with the right reflexive pronoun. You’ll also get a list of common reflexive verbs and plenty of example sentences to see them in action.

- What are reflexive verbs in German?

- Understanding reflexive pronouns in German

- List of common reflexive verbs in German

- Reflexive verbs in action: Sentence examples

- Reflexive verbs in different tenses

- FAQS